Fireflies, or “lightning bugs” as many youth call them are beetles. There isn't just one species of lightning bug, but 2,000 species worldwide, 180 species in the United States, 45+ species in Texas, and 20 species in the Edwards Plateau.

Fireflies have a soft elongated body. Most species are from five to 20 millimeters long. Fireflies in the Amazon are 45 mm long.

A firefly has a flattenend shield that covers the back of its body up to its head. Of course, the feature that everyone knows is bioluminescence, which is the production and emission of light by a chemical process in the body of the insect. There are three different chemicals in the firefly that create the light.

Fireflies live about three weeks as an egg, one to two years as a larva, three weeks as a pupa, and three to four weeks as an adult.

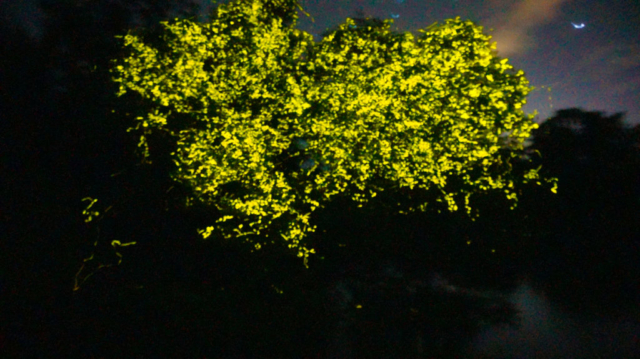

Each firefly species has its own distinctive flash pattern. Flash patterns can differ based on temperature. The color of the flash depends on the temperature and time of night. Colors are yellow, green, and orange.

The flashes you see in the evening are a mating ritual. Female fireflies prefer longer flashes. The males do their thing with the flashes and the females respond with their own (normally shorter) flash series. The flashes are made by three substances in the photic organ by controling the oxygen they breathe in.

Firefly larvae consume snails, earthworms, amd dead insects. They are a good indicator of the health of the environment.

Because of pollution and loss of riparian corridors, fireflies are disappearing. The Arundo monoculture is replacing the varied plants in the riparian areas that fireflies like. This is not good, because a varied plant culture is better for the fireflies (and most other animal species).

Light pollution interferes with the males and females flashing to each other.

Broad spectrum pesticides are a problem for fireflies. If you kill lawn grubs with pesiticide, you kill the firefly larva.

How to help fireflies:

- Introduce nutrients to your soil,

- Till your soil,

- Avoid use of broad spectrum pesticides, especially lawn chemicals,

- Turn off outside lights,

- Advocate for controlling light pollution; suggest Dark Sky policies,

- Don't overmow your lawn,

- Let leaf litter accumulate, and

- A pollinator garden can help fireflies in addition to helping butterflies and moths,

- Females lay eggs in tilled soil. If the soil is hard and compacted, it doesn't work well for egg laying.

Places to see fireflies:

- Places with varied plants and trees in varied heights. Trees give dark cover so fireflies can do their thing. The best environment trees and shrubs in a varied height.

- Stream bed, even if dry part of the time.

- Enchanted Rock State Natural Area

- Fox Canyon Ranch in Jeff Davis County

- Honey Creek in Guadalupe River State Park in Comal County

- The Stewart Property in Bee Cave in Travis County

- Zilker Park, but beware of the poison ivy and poison oak.

Other notes:

Basiclly, if the landscape is dark, the fireflies can flash their light and be seen. Fireflies like soil with water retention.

Flash patterns: for instance, male fireflies flash every four to six seconds, then the females respond within two seconds.

There are two firefly seasons in Texas: one in spring and one in the fall.

Spiders eat fireflies.

Ben is founder of Firefly Conservation & Research at Firefly.org, a firefly conservation and educational non-profit. Firefly.org is currently the internet’s most visited website about fireflies. Ben is a recognized public speaker and science educator whose research work focuses on Texas firefly species. He is working to document the state’s firefly diversity and its natural history regarding their life cycle, preferred habitat and unique flash patterns. His research is helping to illuminate much of this never before collected information about the state’s incredibly rich firefly diversity so that others can work to preserve and enjoy it.

This is a photo submitted to firefly.com. Credit: Katrien Vermeire in the Great Smokies